Option Strategies

Covered Call

Selling the call obligates you to sell stock you already own at strike price A if the option is assigned.

Some investors will run this strategy after they’ve already seen nice gains on the stock. Often, they will sell out-of-the-money calls, so if the stock price goes up, they’re willing to part with the stock and take the profit.

Covered calls can also be used to achieve income on the stock above and beyond any dividends. The goal in that case is for the options to expire worthless.

If you buy the stock and sell the calls all at the same time, it’s called a ”Buy / Write.” Some investors use a Buy / Write as a way to lower the cost basis of a stock they’ve just purchased.

Protective Put

Purchasing a protective put gives you the right to sell stock you already own at strike price A. Protective puts are handy when your outlook is bullish but you want to protect the value of stocks in your portfolio in the event of a downturn. They can also help you cut back on your antacid intake in times of market uncertainty.

Protective puts are often used as an alternative to stop orders. The problem with stop orders is they sometimes work when you don’t want them to work, and when you really need them they don’t work at all. For example, if a stock’s price is fluctuating but not really tanking, a stop order might get you out prematurely. If that happens, you probably won’t be too happy if the stock bounces back. Or, if a major news event happens overnight and the stock gaps down significantly on the open, you might not get out at your stop price. Instead, you’ll get out at the next available market price, which could be much lower.

If you buy a protective put, you have complete control over when you exercise your option, and the price you’re going to receive for your stock is predetermined. However, these benefits do come at a cost. Whereas a stop order is free, you’ll have to pay to buy a put. So it would be nice if the stock goes up at least enough to cover the premium paid for the put.

If you buy stock and a protective put at the same time, this is commonly referred to as a “married put.” For added enjoyment, feel free to play a wedding march and throw rice while making this trade.

Collar

Buying the put gives you the right to sell the stock at strike price A. Because you’ve also sold the call, you’ll be obligated to sell the stock at strike price B if the option is assigned.

You can think of a collar as simultaneously running a protective put and a covered call. Some investors think this is a sexy trade because the covered call helps to pay for the protective put. So you’ve limited the downside on the stock for less than it would cost to buy a put alone, but there’s a tradeoff.

The call you sell caps the upside. If the stock has exceeded strike B by expiration, it will most likely be called away. So you must be willing to sell it at that price.

Cash-Secured Put

Selling the put obligates you to buy stock at strike price A if the option is assigned.

In this instance, you’re selling the put with the intention of buying the stock after the put is assigned. When running this strategy, you may wish to consider selling the put slightly out-of-the-money. If you do so, you’re hoping that the stock will make a bearish move, dip below the strike price, and stay there. That way the put will be assigned and you’ll end up owning the stock. Naturally, you’ll want the stock to rise in the long-term.

The premium received for the put you sell will lower the cost basis on the stock you want to buy. If the stock doesn’t make a bearish move by expiration, you still keep the premium for selling the put. That’s sort of nice, because it’s one of the few instances when you can profit by being wrong.

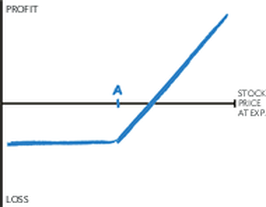

Long Call

A long call gives you the right to buy the underlying stock at strike price A.

Calls may be used as an alternative to buying stock outright. You can profit if the stock rises, without taking on all of the downside risk that would result from owning the stock. It is also possible to gain leverage over a greater number of shares than you could afford to buy outright because calls are always less expensive than the stock itself.

But be careful, especially with short-term out-of-the-money calls. If you buy too many option contracts, you are actually increasing your risk. Options may expire worthless and you can lose your entire investment, whereas if you own the stock it will usually still be worth something. (Except for certain banking stocks that shall remain nameless.)

Long Put

A long put gives you the right to sell the underlying stock at strike price A. If there were no such thing as puts, the only way to benefit from a downward movement in the market would be to sell stock short. The problem with shorting stock is you’re exposed to theoretically unlimited risk if the stock price rises.

But when you use puts as an alternative to short stock, your risk is limited to the cost of the option contracts. If the stock goes up (the worst-case scenario) you don’t have to deliver shares as you would with short stock. You simply allow your puts to expire worthless or sell them to close your position (if they’re still worth anything).

But be careful, especially with short-term out-of-the-money puts. If you buy too many option contracts, you are actually increasing your risk. Options may expire worthless and you can lose your entire investment.

Puts can also be used to help protect the value of stocks you already own. These are called protective puts.

Long Straddle

A long straddle is the best of both worlds, since the call gives you the right to buy the stock at strike price A and the put gives you the right to sell the stock at strike price A. But those rights don’t come cheap.

The goal is to profit if the stock moves in either direction. Typically, a straddle will be constructed with the call and put at-the-money (or at the nearest strike price if there’s not one exactly at-the-money). Buying both a call and a put increases the cost of your position, especially for a volatile stock. So you’ll need a fairly significant price swing just to break even.

Advanced traders might run this strategy to take advantage of a possible increase in implied volatility. If implied volatility is abnormally low for no apparent reason, the call and put may be undervalued. The idea is to buy them at a discount, then wait for implied volatility to rise and close the position at a profit.

Long Strangle

A long strangle gives you the right to sell the stock at strike price A and the right to buy the stock at strike price B.

The goal is to profit if the stock makes a move in either direction. However, buying both a call and a put increases the cost of your position, especially for a volatile stock. So you’ll need a significant price swing just to break even.

The difference between a long strangle and a long straddle is that you separate the strike prices for the two legs of the trade. That reduces the net cost of running this strategy, since the options you buy will be out-of-the-money. The tradeoff is, because you’re dealing with an out-of-the-money call and an out-of-the-money put, the stock will need to move even more significantly before you make a profit.

Long Calendar Spread

W/Calls

A long put gives you the right to sell the underlying stock at strike price A. If there were no such thing as puts, the only way to benefit from a downward movement in the market would be to sell stock short. The problem with shorting stock is you’re exposed to theoretically unlimited risk if the stock price rises.

But when you use puts as an alternative to short stock, your risk is limited to the cost of the option contracts. If the stock goes up (the worst-case scenario) you don’t have to deliver shares as you would with short stock. You simply allow your puts to expire worthless or sell them to close your position (if they’re still worth anything).

But be careful, especially with short-term out-of-the-money puts. If you buy too many option contracts, you are actually increasing your risk. Options may expire worthless and you can lose your entire investment.

Puts can also be used to help protect the value of stocks you already own. These are called protective puts.

A long put gives you the right to sell the underlying stock at strike price A. If there were no such thing as puts, the only way to benefit from a downward movement in the market would be to sell stock short. The problem with shorting stock is you’re exposed to theoretically unlimited risk if the stock price rises.

But when you use puts as an alternative to short stock, your risk is limited to the cost of the option contracts. If the stock goes up (the worst-case scenario) you don’t have to deliver shares as you would with short stock. You simply allow your puts to expire worthless or sell them to close your position (if they’re still worth anything).